Αλλεργία

Με τον όρο αλλεργία εννοείται η παθολογική κατάσταση κατά την οποία ο οργανισμός αντιδρά απέναντι σε αβλαβές περιβαλλοντικές ουσίες, που ονομάζονται αλλεργιογόνα[1]. Πιο ειδικά, η αλλεργία είναι αντίδραση υπερευαισθησίας τύπου Ι στην οποία κύριοι πρωταγωνιστές είναι ειδικά κύταρα του αίματος (βασεόφιλα και μαστοκύτταρα) και ένας ειδικός τύπος αντισώματος (η ανοσοσφαιρίνη Ε).

Ως αλλεργιογόνα μπορούν να δράσουν ορισμένες τροφές όπως τα αυγά, τα ψάρια, τα θαλασσινά ή οι φράουλες, φάρμακα όπως η πενικιλλίνη, οι αντιοροί (πχ αντιτετανικός ορός) σκιαγραφικά σκευάσματα που χρησιμοποιούνται στην ακτινολογία, καλλυντικά, χρώματα, η γύρη διαφόρων φυτών, φτερά και τρίχες διαφόρων ζώων, η σκόνη κ.α.

Τα αλλεργιογόνα φτάνουν στον οργανισμό μέσω της αναπνοής, με επαφή στο δέρμα ή ακόμη με την τροφή ή και ένεση. Όταν ο οργανισμός έρθει σε επαφή με μια ξένη ουσία που δρα ως αλλεργιογόνο, το ανοσοποιητικό του σύστημα βάζει σε λειτουργία τους αμυντικούς μηχανισμούς της χημικής και της κυτταρικής ανοσίας με σκοπό την εξουδετέρωση του αντιγόνου. Έτσι, με πολύ απλά λόγια, την πρώτη φορά που ο οργανισμός θα συναντήσει το αλλεργιογόνο, θα ευαισθητοποιηθεί παράγοντας ανοσοσφαιρίνη Ε η οποία και θα καταλήξει σε ειδικούς υποδοχείς πάνω στα βασεόφιλα και μαστοκύτταρα. Τη δεύτερη (τρίτη κλπ.) φορά που ο οργανισμός θα συναντήσει το ίδιο αλλεργιογόνο τότε η ανοσοσφαιρίνη Ε θα αναγνωρίσει το αλλεργιογόνο και θα ενωθεί με αυτό με αποτέλεσμα την ενεργοποίηση των βασεόφιλων και μαστοκυττάρων. Τα ενεργοποιημένα βασεόφιλα και μαστοκύτταρα θα απελευθερώσουν διάφορες ουσίες που έχουν αποθηκευμένες (π.χ. ισταμίνη) που με τη σειρά τους θα προκαλέσουν μια ταχεία φλεγμονώδη αντίδραση που θα οδηγήσει σε φτάρνισμα, ερυθρότητα, φαγούρα κλπ.[2]

Πηγές

- ↑ Janeway’s Immunobiology (7η έκδοση). Garland Science. November 2007. σελ. 555-83. ISBN 978-0-8153-4123-9.

- ↑ Kay AB (2000). “Overview of ‘allergy and allergic diseases: with a view to the future'”. Br. Med. Bull. 56 (4): 843–64. doi:. PMID 11359624.

Από τη Βικιπαίδεια, την ελεύθερη εγκυκλοπαίδεια

http://el.wikipedia.org/wiki/%CE%91%CE%BB%CE%BB%CE%B5%CF%81%CE%B3%CE%AF%CE%B1

Τροφική αλλεργία

Μηχανισµοί δράσης

Το πρόβλημα των αλλεργιών από τα τρόφιμα αναφέρεται ήδη από τον Ιπποκράτη αλλά μόλις τα τελευταία χρόνια εξετάζεται σε βάθος, αφού έχει πάρει ανησυχητικές διαστάσεις. Πρόσφατοι έλεγχοι του ΕΦΕΤ, οδήγησαν στη διαπίστωση της ύπαρξης αλλεργιογόνων ουσιών σε τεσσάρων ειδών διαφορετικά τρόφιμα (ρύζι, παστέλι με αμύγδαλα, γάλα και σοκολατούχα με φυστίκια και σόγια), οι οποίες όμως δεν αναγράφονταν στη συσκευασία. Γνωρίζουμε ότι οι αλλεργίες αποτελούν εξατομικευμένες δυσμενείς αντιδράσεις του ανοσοποιητικού συστήματος του ανθρώπινου οργανισμού απέναντι σε πρωτεΐνες οι οποίες φυσιολογικά δεν είναι επικίνδυνες. Οι πρωτεΐνες αυτές ονομάζονται αλλεργιογόνα. Ο ανθρώπινος οργανισμός, λοιπόν, αντιλαμβάνεται λανθασμένα τα αλλεργιογόνα ως ξένες, επικίνδυνες ουσίες και αντιδρά εναντίον τους. Αυτή η αντίδραση συνήθως συμβαίνει άμεσα, από λίγα λεπτά ως μια ώρα μετά την κατανάλωση του επίμαχου τροφίμου. Το ανοσιακό μας σύστημα, που ελέγχει την είσοδο ξένων ουσιών για την πιθανότητα αυτές να είναι επιβλαβείς ώστε να τις εξουδετερώσει, μαθαίνει από τις πρώτες ημέρες της ζωής ενός ανθρώπου να μην αντιδρά στις πρωτεΐνες των τροφών (το ανοσιακό δεν αντιδρά επίσης στα σάκχαρα και τα λίπη). Μ’αυτό τον τρόπο προκαλείται ανοσολογική ανοχή, κατάσταση που είναι απαραίτητη για την επιβίωσή μας. Υπό ομαλές συνθήκες, το έντερο μπορεί να γίνει φράγμα ανάμεσα στις τροφές και το ανοσοποιητικό σύστημα, αλλά μια γενετική προδιάθεση μπορεί να κάνει αυτό το φράγμα ανεπαρκές. Έτσι, όταν μια αλλεργιογόνος τροφή περνάει μέσα από το πεπτικό σύστημα, ο οργανισμός σχηματίζει αντισώματα απέναντι σε αυτή την τροφή. Όταν το ευαισθητοποιημένο άτομο καταναλώνει τη συγκεκριμένη τροφή, τότε η πρωτεΐνη-αλλεργιογόνο ενώνεται με το αντίσωμα και τα κύτταρα απελευθερώνουν ορισμένες ουσίες. Η πιο γνωστή από τις ουσίες αυτές λέγεται ισταμίνη και οι απελευθερούμενες ουσίες προκαλούν τα συμπτώματα της τροφικής αλλεργίας.

Τουλάχιστον ένα στα τρία άτομα νομίζει πως είναι αλλεργικό σε ορισμένες τροφές, αλλά στην πραγματικότητα μόνον ένας ή δύο ενήλικες στους εκατό υποφέρουν από αληθινή αλλεργία. Σε όλες τις άλλες περιπτώσεις πρόκειται μόνο για μια απλή μη ανοχή. Είναι εύκολο να μπερδέψουμε μια μη ανοχή σε συγκεκριμένη τροφή με μια αλλεργία, γιατί προκαλούν παρόμοια συμπτώματα. Η μη ανοχή, όμως, δεν εμπλέκει το ανοσοποιητικό σύστημα και είναι πολύ πιο διαδεδομένη από την αλλεργία. Επιπλέον, όποιος δεν ανέχεται κάποια τροφή, μπορεί συνήθως να φάει μια μικρή ποσότητα από την κατηγορούμενη τροφή χωρίς να παρουσιάσει κανένα πρόβλημα, ενώ στον αλλεργικό και η παραμικρή δόση της εχθρικής τροφής είναι αρκετή για να εξαπολυθεί η αντίδραση. Η τροφική αλλεργία είναι συχνά κληρονομική. Όποιος έχει ένα γονιό αλλεργικό, έχει διπλές πιθανότητες να παρουσιάσει την ίδια διαταραχή. Εάν είναι και οι δύο γονείς αλλεργικοί, το ποσοστό ξεπερνά το 60%.

Αλλεργιογόνα τρόφιµα

Κάθε τροφή μπορεί να προκαλέσει τροφική αλλεργία, αλλά λίγες είναι οι τροφές για τις οποίες μπορούμε να είμαστε σίγουροι πως είναι βλαβερές. Οι συνηθέστεροι εισβολείς είναι τα φυστίκια, η σόγια, το αλεύρι από σιτάρι, τα οστρακοειδή, μερικά είδη ψαριών, το αγελαδινό γάλα και τα αυγά. Χαρακτηριστικό παράδειγμα αλλεργίας τροφικής προέλευσης είναι η εμφάνιση εξανθημάτων μετά από κατανάλωση φυστικιών ή ιχθηρών ή δύσπνοια και δυσφορία μετά από ένα ποτήρι γάλα. Η πιο ανησυχητική όμως επίπτωση των αλλεργιών είναι το αναφυλακτικό σοκ που μπορεί να προκαλέσει μέχρι και το θάνατο. Υπολογίζονται για τις ΗΠΑ πάνω από 100 κάθε χρόνο τα θύματα μιας τέτοιας παρενέργειας, όταν τα αντίστοιχα θύματα από τσίμπημα σφήκας δεν ξεπερνούν τα 50. Τα παιδιά πλήττονται από τροφική αλλεργία περίπου δέκα φορές πιο συχνά από τους ενήλικες -τυπικές οι αλλεργίες τους στο γάλα, στο αλεύρι από σιτάρι και στα αυγά. Όσο περισσότερο ωριμάζει το γαστρεντερικό σύστημα, τόσο λιγότερο τείνει να απορροφά τις δυνάμει επιβλαβείς τροφικές ουσίες. Στη μεγάλη πλειοψηφία των παιδιών με τεκμηριωμένες αλλεργικές αντιδράσεις στα αυγά, το γάλα αγελάδος και τη σόγια, οι τροφές αυτές γίνονται τελικά ανεκτές και μπορούν να τις καταναλώνουν στο μέλλον. Σε πολλές περιπτώσεις, οι πιο βαριές αλλεργίες, ιδιαίτερα στους ξηρούς καρπούς και στα οστρακοειδή, κρατούν μιαν ολόκληρη ζωή. Η κακή διατροφή και οι συνθήκες που ευνοούν την εξασθένιση του ανοσοποιητικού συστήματος αυξάνουν τις πιθανότητες που έχει ένας άνθρωπος να αναπτύξει μια τροφική αλλεργία σε κάθε ηλικία. Εκτός από τη γενετική προδιάθεση, ένας δεύτερος λόγος για την εμφάνιση αλλεργίας είναι η συχνότητα κατανάλωσης της τροφής. Στις Σκανδιναβικές χώρες, για παράδειγμα, είναι πολύ συχνή η αλλεργία στο ψάρι (ιδιαίτερα στο βακαλάο), ενώ στην Ιαπωνία στο ρύζι. Στην Ελλάδα εικάζεται ότι υπάρχουν αρκετές αλλεργίες σε όσπρια. Η διάγνωση της τροφικής αλλεργίας από τον αλλεργιολόγο βασίζεται κατά κύριο λόγο στο ακριβές ιστορικό (οι σχετικές πληροφορίες είναι πολύτιμες) και κατά δεύτερο λόγο στις εξετάσεις, δηλαδή δερματικές δοκιμασίες (αλλεργικά tests) και τα RAST – tests (αναζήτηση στον ορό του αίματος των ειδικών IgE-αντισωμάτων).

Οι αλλεργίες που οφείλονται σε κατανάλωση συγκεκριμένων τροφίμων αποτελούν σήμερα ένα μείζον πρόβλημα. Ο ουσιαστικότερος τρόπος αποφυγής τους είναι η πρόληψη, η οποία επιτυγχάνεται με την ενημέρωση των καταναλωτών για τις αλλεργιογόνες ουσίες των τροφίμων, ώστε να αποφεύγεται η κατανάλωσή τους. Σύμφωνα με την Ευρωπαϊκή Αρχή για την Ασφάλεια των Τροφίμων (EFSA) υπάρχουν αρκετά στοιχεία για την αλλεργιογόνο δράση ορισμένων ουσιών και είναι υποχρεωτική η αναγραφή των συστατικών αυτών και των παραγώγων τους στα συσκευασμένα τρόφιμα. Για το λόγο αυτό εκδόθηκε η Οδηγία 2003/89/ΕΚ (που τροποποίησε την Οδηγία 2000/13/ΕΚ), σχετικά με την αναγραφή των συστατικών των τροφίμων, η οποία έχει ήδη ενσωματωθεί στο εθνικό μας δίκαιο (ΦΕΚ 489/Β’/13-4-2005). Τα βασικά σημεία αυτής είναι: Καθορίστηκε κατάλογος συστατικών τροφίμων που θεωρούνται αλλεργιογόνα. Ο κατάλογος αυτός συστάθηκε μετά από αξιολόγηση διαφόρων τροφίμων από την EFSA και θα αναθεωρείται με βάση επιστημονικά κριτήρια. Καταργείται ο κανόνας του 2% για την περίπτωση των αλλεργιογόνων συστατικών τροφίμων, όπου είναι πλέον υποχρεωτική η αναλυτική αναγραφή τους σε οποιοδήποτε ποσοστό και αν βρίσκονται στο τρόφιμο. Γίνεται υποχρεωτική η αναγραφή των αλλεργιογόνων συστατικών με το ειδικό τους όνομα και όχι με αναφορά απλώς στην κατηγορία του συστατικού.

Η σημερινή κατάσταση

Η ανάπτυξη σε όλες τις βιομηχανίες τροφίμων στην Ευρώπη (λόγω της Κοινοτικής Οδηγίας 93/63) συστημάτων HACCP (ασφάλειας τροφίμων), οδήγησε κατά την ανάλυση των πιθανών κινδύνων για τον καταναλωτή στη διερεύνηση και της αλλεργιογόνου δράσης υπολειμμάτων τροφίμων κατά την παραγωγή και τυποποίηση. Η Ευρωπαϊκή Ένωση συνέστησε από το 1997 Επιστημονική Επιτροπή Τροφίμων που σκοπό έχει την διερεύνηση των συνεπειών των αλλεργιών που οφείλονται σε κατανάλωση τροφίμων.

Νομοθεσία για την επισήµανση των αλλεργιογόνων τροφίµων

Η Ευρωπαϊκή Επιτροπή διαπιστώνοντας τη διόγκωση του προβλήματος τα τελευταία 20 χρόνια, κυρίως λόγω της κατανάλωσης από τους Ευρωπαίους καταναλωτές εισαγόμενων προϊόντων που ήσαν σχεδόν άγνωστα ως πρόσφατα (φυστίκια, ακτινίδια κλπ) εξέδωσε στις 10 Νοεμβρίου 2003 την Οδηγία 89 του 2003, η οποία τέθηκε σε εφαρμογή από τις 25 Νοεμβρίου 2004 και ενσωματώθηκε στον Κώδικα Τροφίμων και Ποτών από τον Απρίλιο του 2005. Με βάση την οδηγία αυτή ο παραγωγός ή τυποποιητής τροφίμων είναι υποχρεωμένος να επισημαίνει στη συσκευασία των τροφίμων που παράγει τυχόν ύπαρξη συστατικών που δύνανται να προκαλέσουν αλλεργίες και με βάση το Παράρτημα ΙΙΙ της ως άνω οδηγίας είναι (τα 12 βασικά αλλεργιογόνα):

- Σιτηρά που περιέχουν γλουτένη ή προϊόντα προερχόμενα από αυτά

- Οστρακόδερμα (αστακοί, γαρίδες, καβούρια και προϊόντα τους)

- Αυγά και προϊόντα με βάση τα αυγά

- Ψάρια και προϊόντα με βάση τα ψάρια

- Αραχίδες και προϊόντα τους

- Σόγια και προϊόντα της

- Γάλα και γαλακτοκομικά, συμπεριλαμβανομένης της λακτόζης [η ευαισθησία των ασθενών που είναι αλλεργικοί στο γάλα οφείλεται κατά κύριο λόγο στην β-γαλακτοσφαιρίνη (66-82%) και κατά δεύτερο λόγο στην καζεΐνη (43-57%)]

- Ξηροί καρποί

- Σέλινο και προϊόντα του

- Μουστάρδα και προϊόντα της

- Σουσάμι και προϊόντα του

- Διοξείδιο του θείου και θειώδεις ενώσεις σε συγκεντρώσεις άνω των 10 ppm.

Παραδείγματα διασταυρούμενης επιμόλυνσης (από μίξη ή αλληλεπίδραση τροφίμων) υπάρχουν πολλά: οι σαλάτες μπορεί να προκαλέσουν αλλεργική αντίδραση αν έχουν σέλινο, τα μακαρόνια επιμολύνονται από αυγά, λουκάνικα ή πικάντικα dressings από μουστάρδα, μπισκότα ή σοκολάτα από σησάμι, συσκευασμένα τρόφιμα ή ξύδι από θειώδεις ενώσεις. Τρόφιμα τα οποία δεν συμμορφώνονται προς τις υποδείξεις της Οδηγίας 89/2003 δεν επιτρέπεται να κυκλοφορούν, μετά την 25η Νοεμβρίου 2005 (τρόφιμα τα οποία έχουν ετικετοποιηθεί νωρίτερα, μπορούν να κυκλοφορούν έως εξαντλήσεως του stock). Πάντως, η νομοθεσία δεν καλύπτει αλλεργιογόνα τρόφιμα τα οποία μπορεί να προέκυψαν ως αποτέλεσμα μη σκοπούμενης επιμόλυνσης που συνέβη σε κάποιο στάδιο της παραγωγής ή της μεταφοράς του τροφίμου. Πέραν της Οδηγίας 89/2003 έχουν εκδοθεί άλλες δύο σχετικές Οδηγίες (26/2005, 63/2005) και ένας Κανονισμός 1991/2004. Οι πρώτες αφορούν προσωρινές εξαιρέσεις τροφίμων από την υποχρέωση επισήμανσης (πλήρως ραφιναρισμένο σογιέλαιο, στανόλες και στερόλες σόγιας κ.ά.) ενώ ο κανονισμός αφορά την υποχρέωση στην οινοβιομηχανία να επισημαίνει την ύπαρξη διοξειδίου του θείου στο κρασί εφόσον είναι πάνω από 10 ppm (πρακτικά είναι το αναλυτικό όριο ανίχνευσης).

Τι κάνει η Βιομηχανία;

Η Βιομηχανία Τροφίμων οφείλει: α) να ενημερώνει σωστά τον καταναλωτή β) να διασφαλίζει, στο μέτρο του δυνατού, ότι τα αλλεργιογόνα συστατικά δεν περιέχονται στα τρόφιμα που παράγει. Στα νέα προϊόντα, η ανάπτυξη του προϊόντος πρέπει να βασίζεται σε συνταγή που ελαχιστοποιεί τους κινδύνους εμφάνισης αλλεργιογόνων παραγόντων. Χρειάζονται δοκιμαστικές παραγωγές, δείγματα που διατίθενται για δοκιμή από τους καταναλωτές και ακριβείς πληροφορίες στην ετικέτα. Η παραγωγική διαδικασία πρέπει να καλύπτει όλα τα στάδια: πρώτες ύλες – εφοδιαστική αλυσίδα – κτιριακές εγκαταστάσεις – μηχανήματα. Τα μέτρα εφαρμόζονται σε όλες τις διεργασίες, περιλαμβανομένου του καθαρισμού, της συσκευασίας και της αποθήκευσης. Φυσικά, το σύστημα πρέπει να ελέγχεται και ανασκοπείται τακτικά, ενώ η τήρηση HACCP και GMP θεωρούνται απολύτως απαραίτητες. Συγκεκριμένα, για τον προσδιορισμό των πιθανών κινδύνων από αλλεργιογόνα κατά την παραγωγική διαδικασία, η βιομηχανία οφείλει να διασφαλίζει ότι οι κίνδυνοι ελαχιστοποιούνται στα υλικά που χρησιμοποιεί για την παραγωγή ενός τροφίμου (α’ ύλες, χρωστικές, αρωματικές ύλες), στα υλικά συσκευασίας και στα υπολείμματα που έχουν μείνει στη γραμμή παραγωγής από προηγούμενο προϊόν. Οι κίνδυνοι ελλοχεύουν και σχετίζονται όχι μόνο με τα υλικά, αλλά και με το κτίριο, τα μηχανήματα, τα εργαλεία, τους εργαζομένους και τα μέσα μεταφοράς. Με βάση και τις αρχές του HACCP, η Βιομηχανία Τροφίμων καλείται ειδικότερα να:

- εντοπίζει οποιονδήποτε κίνδυνο μπορεί να προβλεφθεί, εξαλειφθεί ή μειωθεί σε αποδεκτά επίπεδα

- προσδιορίζει τα κρίσιμα σημεία ελέγχου (ccp)

- καθιερώνει όρια, πέραν των οποίων η παρουσία αλλεργιογόνων παραγόντων συνιστά κίνδυνο

- διαπιστώνει τα τυχόν προβλήματα στα ccp

- αναλαμβάνει διορθωτικές ενέργειες

- επιβεβαιώνει ότι οι ως άνω ενέργειες είναι αποτελεσματικές.

Σε αρκετές χώρες (π.χ. Ηνωμένο Βασίλειο, Ολλανδία, Αυστραλία) υπάρχουν συγκεκριμένες κατευθυντήριες οδηγίες για τον έλεγχο των αλλεργιογόνων και την ενημέρωση του καταναλωτή. Ένα παράδειγμα είναι η έμφαση στην αναγκαιότητα της βιομηχανίας ζυμαρικών να διαθέτει χωριστές γραμμές παραγωγής για τα μακαρόνια (που βασίζονται στο σιμιγδάλι) και τις χυλοπίτες (που βασίζονται στο σιτάρι, αλλά περιέχουν και αυγά). Η τεχνολογία χρησιμοποιεί πλέον τεχνικές food matrix ή στοιχεία της σύνθεσης (οξύτητα, αλατότητα) για να προσδιορίσει την ύπαρξη αλλεργιογόνων σε μικρές ποσότητες.

Στο εργαστήριο

Η CEN (European Committee for Standardization) συνέστησε στις αρχές του 2003 την Ομάδα Εργασίας WG12 (υπάγεται στην ΤC 275, που έχει αντικείμενο τα Τρόφιμα) για τον καθορισμό μεθόδων για την ανίχνευση αλλεργιογόνων ουσιών. Αναλυτικές τεχνικές έχουν αναπτυχθεί μόλις την τελευταία 5ετία, γι’αυτό και η WG12 προχώρησε στην παράλληλη διερεύνηση της αλλεργιογόνου δράσης τροφίμων τόσο με ανοσοχημικές μεθόδους όσο και με μεθόδους Μοριακής Βιολογίας. Με αυτές τις μεθόδους έχουν αναπτυχθεί και ειδικές εφαρμογές για τον προσδιορισμό νοθείας των τροφίμων.

Εξειδικευμένα Εργαστήρια στην Ελλάδα

Η ανάγκη συμμόρφωσης της Ελληνικής Βιομηχανίας Τροφίμων με τη νέα νομοθεσία, έκανε επιτακτική την ανάγκη δημιουργίας εξειδικευμένων εργαστηρίων για την ανίχνευση αλλεργιογόνων στα συσκευασμένα τρόφιμα. Έτσι, εργαστηριακά, τα τελευταία χρόνια έχουν αναπτυχθεί ευαίσθητες αναλυτικές τεχνικές: ELISA (ανοσοχημική / antibodies) PCR (μέθοδος Μοριακής Βιολογίας, DNA-based) LC-MS. Επίσης, το Γενικό Χημείο του Κράτους έχει προχωρήσει σε διεργαστηριακές δοκιμές για φυστίκι και γλουτένη. Πολλά από τα αντισώματα που χρησιμοποιούνται σε ανοσολογικές τεχνικές παράγονται με την επαναλαμβανόμενη ανοσοποίηση κατάλληλων ζώων (π.χ. κουνέλια), αφού εισαχθεί στον οργανισμό τους εναιώρημα του επιθυμητού αντιγόνου. Ο ορός τους μαζεύεται την ημέρα όπου έχουμε τη μέγιστη παραγωγή αντισωμάτων, δίνοντας συγκεντρώσεις IgG αντισωμάτων από 1 έως και 10 mg/ml. Τα αντισώματα που παίρνουμε είναι πολυκλωνικά (πολλές διαφορετικές ειδικότητες).

Βιβλιογραφία

- 1. Σειραγάκης Γ., Ιλαντζής Σπ.: Αλλεργιογόνα, περιοδικό “Τρόφιμα και Ποτά”, Νοέμ. 2006.

- 2. Σειραγάκης Γ.: Συστήματα Ασφάλειας Τροφίμων σε ελαιουργεία και τυποποιητικές μονάδες. Πρακτικά ημερίδας Ποιότητα Ελαιολάδου, ΓΧΚ, Αθήνα 2002

- 3. Τροφικές Αλλεργίες από την πλευρά του αλλεργιολόγου ιατρού. Καθ/τής Καλογερομήτρος Δημ., ΓΠΝ Αττικόν , ημερίδα ΕΕΧ για την Ιχνηλασιμότητα στα Τρόφιμα, Αθήνα 2005.

- 4. Οrtolani, Ispano, Scibilia and Pastorello: Introducing chemists to Food Allergy, Allergy 2001 56 pp 5‑8.

- 5. Οδηγία 2003/89/ΕΚ: του ΕΚ και του Συμβουλίου της 10ης Νοεμβρίου 2003 για την αναγραφή συστατικών των τροφίμων. L 308 25.11.2003 σελ. 15-19.

- 6. Guidance on allergen control and consumer information (draft), FSA, UK, Σεπτ. 2005. http://www.food.gov.uk/

- 7. Εuropa Research RTD info: The Allergy Enigma. Magazine on European Research No 41.

- 8. Bremer M.: Rapid Tests for Allergen Detection. Πρακτικά 3ου Συμπόσιου: Ποιότητα και ανταγωνιστικότητα στις επιχειρήσεις τροφίμων, Αθήνα 6-8/11/2003 σελ. 482-492.

- 9. Roux Ken. H et al : Detection and stability of the major almond allergen in foods J.Agric.Food Chem. 2001, 49 2131-2136.

- 10. Thirumala-Devi K. and Reddy D. V. R.: Application of ELISA for cost-effective analysis of aflatoxins in foods and feeds. FoodInfo, http://www.foodsciencecentral.com/library.html#ifis/13446.

Από τη Βικιπαίδεια, την ελεύθερη εγκυκλοπαίδεια

Αναφυλαξία

| Αναφυλαξία | |

|---|---|

Angioedema of the face such that the boy is unable to open his eyes. This reaction was due to an allergen exposure. |

|

| Ταξινόμηση ICD-10 | T78.2 |

| Ταξινόμηση ICD-9 | 995.0 |

| DiseasesDB | 29153 |

| MedlinePlus | 000844 |

| eMedicine | med/ |

| MeSH | D000707 |

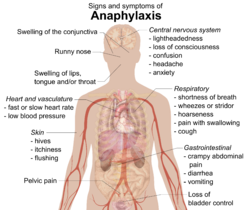

Η αναφυλαξία είναι μια σοβαρή αλλεργική αντίδραση που αρχίζει αιφνίδια και μπορεί να προκαλέσει θάνατο.[1] Η αναφυλαξία συνήθως παρουσιάζει διάφορα συμπτώματα που συμπεριλαμβάνουν εξανθήματα με κνησμό, οίδημα του λαιμού και χαμηλή αρτηριακή πίεση. Τα συνήθη αίτια περιλαμβάνουν δαγκώματα από έντομα, κατανάλωση τροφίμων και λήψη φαρμάκων.

Την αναφυλαξία προκαλεί η απελευθέρωση πρωτεϊνών από ορισμένων ειδών λευκά αιμοσφαίρια. Οι πρωτεΐνες αυτές είναι ουσίες που μπορούν να ξεκινήσουν μια αλλεργική αντίδραση ή να την οξύνουν. Η απελευθέρωσή τους μπορεί να προκληθεί είτε από αντίδραση του ανοσοποιητικού συστήματος ή από κάποια άλλη αιτία που δεν σχετίζεται με το ανοσοποιητικό σύστημα. Η διάγνωση της αναφυλαξίας γίνεται βάσει των συμπτωμάτων και των ευρημάτων του ατόμου. Πρωταρχική θεραπεία είναι η ένεση επινεφρίνης, η οποία μερικές φορές συνδυάζεται με άλλες φαρμακευτικές αγωγές.

Περίπου το 0,05–2% του παγκόσμιου πληθυσμού αντιμετωπίζουν περιστατικό αναφυλαξίας κάποια στιγμή της ζωής του. Το ποσοστό αυτό φαίνεται να παρουσιάζει αύξηση. Ο όρος προέρχεται από τις ελληνικές λέξεις «ἀνά» και «φύλαξις».

Ευρήματα και συμπτώματα

Η αναφυλαξία συνήθως παρουσιάζει πολλά διαφορετικά συμπτώματα σε διάστημα λεπτών ή ωρών.[2][3] Τα συμπτώματα εμφανίζονται κατά μέσο όρο σε διάστημα 5 με 30 λεπτών αν η αιτία πρόκλησής τους είναι κάποια ουσία που εισέρχεται στο σώμα απευθείας από την κυκλοφορία του αίματος (ενδοφλέβια). Αν η αιτία είναι η κατανάλωση κάποιου φαγητού, το μέσο διάστημα είναι 2 ώρες. [4] Οι συχνότερες περιοχές που προσβάλλονται είναι: το δέρμα (80–90%), οι πνεύμονες και οι αναπνευστικοί οδοί (70%), το στομάχι και τα έντερα (30–45%), η καρδιά και τα αιμοφόρα αγγεία (10–45%), και το κεντρικό νευρικό σύστημα (10–15%).[3] Συνήθως συμμετέχουν δύο ή περισσότερα από αυτά τα συστήματα.[5]

Δέρμα

Τα συμπτώματα συνήθως περιλαμβάνουν έπαρση του δέρματος σε μορφή εξογκωμάτων (κνίδωση), κνησμό, κοκκίνισμα στο πρόσωπο ή το δέρμα (ερύθημα) ή πρησμένα χείλη.[6] Όσα άτομα εκδηλώνουν οίδημα κάτω από το δέρμα (αγγειοοίδημα) ενδέχεται να νιώσουν στο δέρμα τους κάψιμο αντί για κνησμό.[4] Η γλώσσα ή ο λαιμός μπορεί να παρουσιάσουν οίδημα μέχρι και στο 20% των περιπτώσεων.[7] Άλλα χαρακτηριστικά μπορεί να περιλαμβάνουν καταρροή και οίδημα του βλεννογόνου υμένα στην επιφάνεια του ματιού και του βλεφάρου (επιπεφυκώς υμένας).[8] Το δέρμα μπορεί επίσης να παρουσιάσει ένα μπλε χρωμάτισμα (κυάνωση) λόγω της έλλειψης οξυγόνου.[8]

Αναπνευστικό

Τα συμπτώματα και τα ευρήματα στο αναπνευστικό σύστημα περιλαμβάνουν δύσπνοια, δυσκολία στην αναπνοή που συνοδεύεται από οξύ ήχο (εκπνευστικοί συριγμοί) ή δυσκολία στην αναπνοή που συνοδεύεται από οξύ αμβλύ (εισπνευστικοί συριγμοί) ήχο.[6] Η αναπνοή που παράγει αμβλύ ήχο οφείλεται, συνήθως, σε μυϊκούς σπασμούς των κατώτερων αεραγωγών (βρογχικοί μύες).[9] Η αναπνοή που παράγει οξύ ήχο οφείλεται σε οίδημα των ανώτερου αεραγωγού, το οποίο προκαλεί στένωση των αναπνευστικών οδών.[8] Μπορεί επίσης να παρουσιαστεί βραχνάδα, πόνος κατά την κατάποση ή βήχας.[4]

Καρδιαγγειακό

Τα αιμοφόρα αγγεία της καρδιάς ενδέχεται να συσταλούν ξαφνικά (σπασμός στεφανιαίων αρτηριών) λόγω της απελευθέρωσης ισταμίνης από ορισμένα κύτταρα στην καρδιά.[9] Αυτό προκαλεί διακοπή της ροής του αίματος προς την καρδιά (έμφραγμα του μυοκαρδίου), που με τη σειρά της μπορεί να προκαλέσει το θάνατο κυττάρων της καρδιάς, μια υπερβολικά αυξημένη ή μειωμένη συχνότητα χτύπων της καρδιάς (καρδιακή δυσρυθμία), ή την πλήρη διακοπή της λειτουργίας της (ανακοπή καρδιάς).[3][5] Τα άτομα που πάσχουν από στεφανιαία νόσο αντιμετωπίζουν μεγαλύτερο κίνδυνο για καρδιακές επιπτώσεις από την αναφυλαξία.[9] Αν και ο υψηλός καρδιακός ρυθμός που προκαλεί η χαμηλή αρτηριακή πίεση είναι συχνότερο φαινόμενο,[8] το 10% των ανθρώπων που προσβάλλονται από αναφυλαξία είναι πιθανό να παρουσιάσει χαμηλό καρδιακό ρυθμό (βραδυκαρδία) σε συνδυασμό με χαμηλή αρτηριακή πίεση. (Ο συνδυασμός χαμηλού καρδιακού ρυθμού και χαμηλής αρτηριακής πίεσης είναι γνωστός ως αντανακλαστικό Bezold–Jarisch).[10] Το άτομο ενδέχεται να νιώσει ζαλάδα ή να χάσει τις αισθήσεις του λόγω πτώσης της αρτηριακής πίεσης. Η χαμηλή πίεση μπορεί να προκληθεί από τη διεύρυνση των αιμοφόρων αγγείων (κυκλοφορική καταπληξία) ή την ανεπάρκεια των κοιλιών της καρδιάς (καρδιογενής καταπληξία). [9] Σε σπάνιες περιπτώσεις, η υπερβολικά χαμηλή αρτηριακή πίεση μπορεί να είναι το μοναδικό εύρημα αναφυλαξίας.[7]

Άλλα

Πιθανά συμπτώματα στο στομάχι και τα έντερα είναι: πόνος κράμπας στην κοιλιά, διάρροια και εμετός.[6] Το άτομο μπορεί να αντιμετωπίσει σύγχυση στη σκέψη, να χάσει τον έλεγχο της ουροδόχου κύστης του και να παρουσιάσει πόνο στη λεκάνη παρόμοιο με αυτών της κράμπας στη μήτρα. [6][8] Η διεύρυνση των αιμοφόρων αγγείων γύρω από τον εγκέφαλο μπορεί να προκαλέσει πονοκεφάλους.[4] Το άτομο μπορεί επίσης να νιώσει ανησυχία ή να έχει την αίσθηση ότι θα πεθάνει. [5]

Αιτιολογία

Η αναφυλαξία μπορεί να προκληθεί από την αντίδραση του σώματος σε σχεδόν οποιαδήποτε ξένη ουσία.[11] Τα συνήθη ερεθίσματα είναι δαγκώματα ή τσιμπήματα από έντομα, φαγητά και φάρμακα.[10][12] Τα φαγητά αποτελούν τις συχνότερες αιτίες πρόκλησης στα παιδιά και τους νεαρούς ενήλικες. Στους μεγαλύτερους σε ηλικία ενήλικες οι πιο συχνές αιτίες είναι τα φάρμακα και τα δαγκώματα και.[5] Λιγότερο συχνές αιτίες πρόκλησης περιλαμβάνουν φυσικούς παράγοντες, βιολογικούς παράγοντας (όπως το σπέρμα), το λατέξ, τις ορμονικές μεταβολές, τα πρόσθετα τροφίμων (όπως το γλουταμινικό μονονάτριο και οι χρωστικές ουσίες) και φάρμακα που χορηγούνται στο δέρμα (τοπικά).[8] Η σωματική άσκηση και οι ακραίες θερμοκρασίες (είτε η ζέστη είτε το κρύο) μπορούν επίσης να επιφέρουν αναφυλαξία, προκαλώντας την απελευθέρωση χημικών ουσιών από ορισμένα κύτταρα ιστών (μαστοκύτταρα), οι οποίες ξεκινούν την αλλεργική αντίδραση.[5][13] Η αναφυλαξία που προκαλείται από την άσκηση συνδέεται συχνά με την κατανάλωση ορισμένων φαγητών.[4] Αν η αναφυλαξία επέλθει ενώ το άτομο βρίσκεται υπό την επήρεια αναισθησίας, οι συχνότερες αιτίες οφείλονται σε ορισμένα φάρμακα που χορηγούνται για να επιφέρουν παράλυση (παράγοντες νευρομυϊκού αποκλεισμού), αντιβιοτικά και λατέξ.[14] Στο 32-50% των περιπτώσεων, η αιτία δεν είναι γνωστή (ιδιοπαθής αναφυλαξία).[15]

Τρόφιμα

Πολλά τρόφιμα είναι ικανά να προκαλέσουν αναφυλαξία, ακόμα και όταν ένα τρόφιμο καταναλώνεται για πρώτη φορά.[10] Σε Δυτικές κοινωνίες, οι πιο συχνές αιτίες είναι η κατανάλωση ή η επαφή με φιστίκια, σιτάρι, ξηρούς καρπούς, οστρακόδερμα, ψάρια, γάλα και αυγά.[3][5] Στη Μέση Ανατολή, το σουσάμι είναι φαγητό που συχνά προκαλεί αναφυλαξία. Στην Ασία, το ρόλο αυτό παίζουν το ρύζι και τα ρεβίθια.[5] Οι σοβαρές περιπτώσεις συνήθως προκαλούνται από την κατανάλωση του τροφίμου,[10] ενώ πολλοί άνθρωποι παρουσιάζουν έντονη αντίδραση όταν το τρόφιμο που ευθύνεται για την αντίδραση έρχεται σε επαφή με κάποιο μέρος του σώματος. Τα παιδιά μπορεί να ξεπεράσουν κάποιες αλλεργίες. Μέχρι την ηλικία των 16, το 80% των παιδιών που παρουσιάζουν αναφυλαξία στο γάλα ή τα αυγά και το 20% που παρουσιάζουν ένα μεμονωμένο περιστατικό αναφυλαξίας στα φιστίκια καταφέρνουν να καταναλώσουν αυτά τα φαγητά χωρίς προβλήματα.[11]

Φάρμακα

Οποιοδήποτε φάρμακο μπορεί να προκαλέσει αναφυλαξία. Συχνότερη περίπτωση αποτελούν τα αντιβιοτικά β-λακτάμες (όπως η πενικιλίνη), ακολουθούμενα από την ασπιρίνη και τα ΜΣΑΦ (Μη Στεροειδή Αντιφλεγμονώδη).[3][16] Αν ένα άτομο είναι αλλεργικό σε κάποιο ΜΣΑΦ, συνήθως μπορεί να χρησιμοποιήσει κάποιο διαφορετικό, χωρίς να προκληθεί αναφυλαξία.[16] Άλλες συνήθεις αιτίες αναφυλαξίας είναι η χημειοθεραπεία, τα εμβόλια, η πρωταμίνη (που βρίσκεται στο σπέρμα) και φάρμακα που παρασκευάζονται από βότανα.[5][16] Μερικά φάρμακα, όπως η βανκομυκίνη, η μορφίνη και κάποιες ουσίες που χρησιμοποιούνται για τη βελτίωση ποιότητας εικόνων που προκύπτουν από ακτίνες Χ (σκιαγραφικοί παράγοντες) προκαλούν αναφυλαξία μέσα από τη φθορά ορισμένων κυττάρων στους ιστούς, που με τη σειρά τους απελευθερώνουν ισταμίνη (αποκοκκίωση).[10]

Η συχνότητα μιας τέτοιας αντίδρασης σε κάποιο φάρμακο εξαρτάται εν μέρει στο πόσο συχνά χορηγείται και εν μέρει στον τρόπο λειτουργίας του φαρμάκου μέσα στο σώμα.[17] Αναφυλαξία στις πενικιλίνες ή στις κεφαλοσπορίνες επέρχεται μόνο αφού δεσμευτούν σε πρωτεΐνες στο εσωτερικό του σώματος, ενώ μερικές δεσμεύονται πιο εύκολα από άλλες.[4] Αναφυλαξία στην πενικιλίνη εμφανίζεται μία φορά στις 2,000 με 10,000 περιπτώσεις ατόμων στα οποία χορηγείται. Το πολύ ένας στους 50,000 ανθρώπους που λαμβάνουν πενικιλίνη ως θεραπευτική αγωγή πεθαίνει.[4] Αναφυλαξία στην ασπιρίνη και τα ΜΣΑΦ παρουσιάζει ένας στους 50,000 ανθρώπους.[4] Αν κάποιος παρουσιάσει αντίδραση στις πενικιλίνες, ο κίνδυνος να παρουσιάσει αντίδραση στις κεφαλοσπορίνες είναι μεγαλύτερος, αλλά παραμένει μικρότερος του ένα στα 1000.[4] Παλαιότερα φάρμακα που χρησιμοποιούνται για τη βελτίωση των εικόνων που προκύπτουν από τις ακτίνες Χ (σκιαγραφικοί παράγοντες) προκαλούσαν αντιδράσεις στο 1% των περιπτώσεων. Οι νεότεροι σκιαγραφικοί παράγοντες χαμηλότερης πυκνότητας προκαλούν αντιδράσεις στο 0,04% των περιπτώσεων.[17]

Δηλητήριο

Το δηλητήριο από έντομα που τσιμπούν ή δαγκώνουν, όπως είναι οι μέλισσες και οι σφίγγες (τάξη υμενόπτερων) ή τα ημίπτερα δολοφόνοι (υποοικογένεια Triatominae) μπορεί να προκαλέσει αναφυλαξία.[3][18] Αν ένα άτομο έχει παρουσιάσει αντίδραση στο δηλητήριο στο παρελθόν και η αντίδραση εκτεινόταν πέρα της περιοχής του τσιμπήματος, διατρέχει μεγαλύτερο κίνδυνο να παρουσιάσει αναφυλαξία στο μέλλον.[19][20] Ωστόσο, οι μισοί άνθρωποι που πεθαίνουν από αναφυλαξία δεν έχουν παρουσιάσει προηγούμενη συστημική αντίδραση.[21]

Παράγοντες κινδύνου

Οι άνθρωποι με ατοπικές ασθένειες όπως είναι το άσθμα, η δερματίτιδα ή η αλλεργική ρινίτιδα διατρέχουν υψηλό κίνδυνο αναφυλαξίας λόγω τροφίμων, λατέξ και σκιαγραφικών παραγόντων. Αυτοί οι άνθρωποι, ωστόσο, δε διατρέχουν μεγαλύτερο κίνδυνο από την ενδοφλέβια χορήγηση φαρμάκων ή τα τσιμπήματα.[5][10] Μία έρευνα που πραγματοποιήθηκε σε παιδιά με αναφυλαξία ανακάλυψε ότι το 60% είχε ιστορικό προηγούμενων ατοπικών ασθενειών. Πάνω από το 90% των παιδιών που πεθαίνουν από αναφυλαξία πάσχουν από άσθμα.[10] Όσοι άνθρωποι αντιμετωπίζουν διαταραχές που προκαλούνται από τον εξαιρετικά μεγάλο αριθμό μαστοκυττάρων στους ιστούς τους (μαστοκυττάρωση), όπως και εκείνοι που ανήκουν σε υψηλότερο κοινωνικοοικονομικό επίπεδο, αντιμετωπίζουν αυξημένο κίνδυνο.[5][10] Όσο μεγαλύτερο χρονικό διάστημα περάσει από την προηγούμενη έκθεση στον παράγοντα που προκαλεί την αναφυλαξία, τόσο μικρότερος είναι ο κίνδυνος κάποιας νέας αντίδρασης.[4]

Μηχανισμοί

Η αναφυλαξία είναι μια οξεία αλλεργική αντίδραση που ξεκινάει ξαφνικά και επηρεάζει πολλά συστήματα του σώματος.[1][22] Προκαλείται από την απελευθέρωση φλεγμονωδών μεσολαβητών και κυτοκινών από μαστοκύτταρα και βασεόφιλα. Η απελευθέρωσή τους, συνήθως, προκαλείται από την αντίδραση του ανοσοποιητικού συστήματος, ωστόσο μπορεί να προκληθεί και από τη φθορά αυτών των κυττάρων που δε σχετίζεται με κάποια ανοσολογική αντίδραση.[22]

Ανοσολογικοί

Όταν η αναφυλαξία προκαλείται από ανοσολογική αντίδραση, η ανοσοσφαιρίνη Ε (IgE) δεσμεύεται στην ξένη ουσία και ξεκινάει την αλλεργική αντίδραση (αντιγόνο). Ο συνδυασμός της δεσμευμένης στο αντιγόνο IgE ενεργοποιεί τους FcεRI υποδοχείς στα μαστοκύτταρα και τα βασεόφιλα. Τα μαστοκύτταρα αντιδρούν απελευθερώνοντας φλεγμονώδεις μεσολαβητές, όπως είναι η ισταμίνη. Αυτοί οι μεσολαβητές αυξάνουν τη συστολή των λείων μυών των βρόγχων, προκαλούν την διεύρυνση των αιμοφόρων αγγείων (αγγειοδιαστολή), αυξάνουν τη διαρροή υγρών από τα αιμοφόρα αγγεία και καταστέλλουν τη δράση του μυοκαρδίου.[4][22] Υπάρχει, επίσης, ένας ανοσολογικός μηχανισμός που δεν εξαρτάται από την IgE, ωστόσο δεν είναι γνωστό αν λειτουργεί στον άνθρωπο.[22]

Μη ανοσολογικοί

Όταν η αναφυλαξία δεν προκαλείται από ανοσολογική αντίδραση, τότε την προκαλεί ένας παράγοντας που φθείρει άμεσα τα μαστοκύτταρα και τα βασεόφιλα, κάνοντάς τα να απελευθερώσουν ισταμίνη και άλλες ουσίες, οι οποίες προκαλούν, συνήθως, αλλεργικές αντιδράσεις (αποκοκκίωση). Οι παράγοντες που μπορούν να φθείρουν αυτά τα κύτταρα περιλαμβάνουν τα μέσα σκιαγράφησης για ακτίνες Χ, τα οπιοειδή, την ακραία θερμοκρασία (ζέστη ή κρύο) και τις δονήσεις.[13][22]

Διάγνωση

Η διάγνωση της αναφυλαξίας γίνεται με βάση κλινικά στοιχεία.[5] Όταν οποιοδήποτε από τα ακόλουθα τρία παρατηρηθεί εντός λίγων λεπτών/ωρών από την έκθεση σε κάποιο αλλεργιογόνο, είναι πολύ πιθανό ότι το άτομο έχει αναφυλαξία:[5]

- Δερματικός ερεθισμό ή ερεθισμός των βλεννογόνων ιστών, και είτε αναπνευστική δυσχέρεια είτε χαμηλή αρτηριακή πίεση

- Δύο ή περισσότερα από τα ακόλουθα συμπτώματα:-

- α. Δερματικός ερεθισμός ή βλέννα

- β. Αναπνευστική δυσχέρεια

- γ. Χαμηλή αρτηριακή πίεση

- δ. Γαστρεντερικά συμπτώματα

- Χαμηλή αρτηριακή πίεση μετά από έκθεση σε γνωστό αλλεργιογόνο

Εάν ένα άτομο έχει κακή αντίδραση σε τσίμπημα εντόμου ή σε φαρμακευτική αγωγή, ενδεχομένως να ενδείκνυνται αιματολογικές εξετάσεις για τρυπτάση ή ισταμίνη (απελευθερώνεται από τα μαστοκύτταρα) για την διάγνωση της αναφυλαξίας. Ωστόσο, αυτές οι εξετάσεις δεν είναι πολύ κατατοπιστικές εάν το αίτιο έγκειται σε τρόφιμο ή εάν το άτομο έχει φυσιολογική αρτηριακή πίεση,[5] και δεν μπορεί να αποκλειστεί η διάγνωση της αναφυλαξίας.[11]

Κατηγορίες

Υπάρχουν τρεις κύριες κατηγορίες αναφυλαξίας. Το αναφυλακτικό σοκ εμφανίζεται όταν τα αιμοφόρα αγγεία διευρυνθούν στο μεγαλύτερο μέρος του σώματος (συστηματική αγγειοδιαστολή), η οποία προκαλεί χαμηλή αρτηριακή πίεση που είναι τουλάχιστον 30% χαμηλότερη από την κανονική πίεση του αίματος του ατόμου ή κάτω από το 30% των φυσιολογικών τιμών. [7] Η διφασική αναφυλαξία διαγιγνώσκεται όταν τα συμπτώματα επιστρέψουν μέσα σε 1 έως 72 ώρες, ακόμα κι εάν το άτομο δεν είχε νέα επαφή με το αλλεργιογόνο που προκάλεσε την πρώτη αντίδραση.[5] Ορισμένες μελέτες υποστηρίζουν ότι το 20% των περιπτώσεων αναφυλαξίας είναι διφασικές.[23] Τα συμπτώματα συνήθως επιστρέφουν εντός 8 ωρών.[10] Η δεύτερη αντίδραση αντιμετωπίζεται με τον ίδιο τρόπο όπως η πρώτη αναφυλαξία.[3] Ψευδοαναφυλαξία ή αναφυλακτοειδείς αντιδράσεις είναι οι παλαιότερες ονομασίες για την αναφυλαξία που δεν οφείλεται σε αλλεργική αντίδραση, αλλά οφείλεται σε άμεση ζημιά των σιτευτικών κυττάρων (αποκοκκίωση μαστοκυττάρων).[10][24] Το σημερινό όνομα που χρησιμοποιείται από τον Παγκόσμιο Οργανισμό Αλλεργιολογίας είναι “non-immune anaphylaxis” (μη ανοσολογική αναφυλαξία)[24], ενώ υποστηρίζεται πως παλαιότεροι όροι δεν πρέπει να χρησιμοποιούνται πλέον.[10]

Αλλεργικά τεστ

Τα αλλεργικά τεστ μπορούν να βοηθήσουν να προσδιοριστεί το αίτιο της αναφυλακτικής αντίδρασης ενός ατόμου. Δερματικά τεστ αλλεργίας (όπως τα δερματικά τεστ επικόλλησης)είναι διαθέσιμα για ορισμένες τροφές και δηλητηριώδεις ουσίες.[11] Οι αιματολογικές εξετάσεις για συγκεκριμένα αντισώματα μπορεί να είναι χρήσιμες για να επιβεβαιωθεί αλλεργία σε γάλα, αυγά, φιστίκια, καρπούς δέντρων και ψάρια.[11] Τα δερματικά τεστ μπορούν να επιβεβαιώσουν αλλεργία στην πενικιλίνη, αλλά δεν υπάρχουν δερματικά τεστ για άλλες φαρμακευτικές ουσίες. [11] Μη ανοσολογικές μορφές αναφυλαξίας μπορούν να διαγνωστούν μόνο με τον έλεγχο του ιατρικού ιστορικού του ατόμου ή εκθέτοντας το άτομο σε αλλεργιογόνο που μπορεί να είχε προκαλέσει αντίδραση στο παρελθόν. Δεν υπάρχουν δερματικά ή αιματολογικά τεστ για μη ανοσολογική αναφυλαξία.[24]

Διαφορική διάγνωση

Ορισμένες φορές, μπορεί να είναι δύσκολο να ξεχωρίσουμε την αναφυλαξία από το άσθμα, τη λιποθυμία λόγω έλλειψης οξυγόνου (συγκοπή) και τις κρίσεις πανικού.[5] Οι άνθρωποι με άσθμα συνήθως δεν παρουσιάζουν κνησμό, στομαχικά ή εντερικά συμπτώματα. Όταν ένα άτομο λιποθυμά, το δέρμα είναι χλωμό και δεν έχει εξάνθημα. Ένα άτομο που παθαίνει κρίση πανικού μπορεί να έχει ερεθισμένο δέρμα, αλλά δεν έχει κνιδώσεις.[5] Άλλες παθήσεις που μπορεί να παρουσιάσουν παρόμοια συμπτώματα περιλαμβάνουν την τροφική δηλητηρίαση από χαλασμένο ψάρι (σκοµβροείδωση) και τη μόλυνση από συγκεκριμένα παράσιτα (ανισακίαση).[10]

Πρόληψη

Ο συνιστώμενος τρόπος για την πρόληψη της αναφυλαξίας είναι να αποφευχθεί οτιδήποτε προκάλεσε την αντίδραση στο παρελθόν. Όταν αυτό δεν είναι δυνατό, ενδέχεται να υπάρχουν θεραπείες ώστε να βοηθήσουν το σώμα να σταματήσει να αντιδρά σε ένα γνωστό αλλεργιογόνο (απευαισθητοποίηση). Η θεραπεία του ανοσοποιητικού συστήματος (ανοσοθεραπεία) με δηλητηριώδεις ουσίες υμενόπτερων είναι αποτελεσματική για την απευαισθητοποίηση του 80-90% των ενηλίκων και του 98% των παιδιών κατά των αλλεργιών που οφείλονται σε μέλισσες, σφήκες, αγριομέλισσες, κηφήνες και κόκκινα μυρμήγκια Η ανοσοθεραπεία από το στόμα μπορεί να είναι αποτελεσματική για την απευαισθητοποίηση ορισμένων ατόμων σε ορισμένα τρόφιμα όπως γάλα, αυγά, ξηρούς καρπούς και φιστίκια. Ωστόσο, αυτές οι θεραπείες έχουν συχνά παρενέργειες. Η απευαισθητοποίηση είναι επίσης εφικτή για πολλές φαρμακευτικές ουσίες, ωστόσο οι περισσότεροι άνθρωποι θα πρέπει απλώς να αποφεύγουν το φάρμακο που τους προκαλεί το πρόβλημα. Σε όσους που παρουσιάζουν αντίδραση στο λατέξ, μπορεί να είναι σημαντικό να αποφεύγουν τα τρόφιμα που περιέχουν ουσίες παρόμοιες με εκείνη που προκάλεσε την αντίδραση του ανοσοποιητικού (συσχετιζόμενες τροφές), όπως μεταξύ άλλων αβοκάντο, μπανάνες και πατάτες .[5]

Διαχείριση

Η αναφυλαξία είναι ένα επείγον ιατρικό περιστατικό όπου μπορεί να απαιτηθεί η λήψη μέτρων διάσωσης, όπως διάνοιξη αποφραγμένων αεραγωγών, χορήγηση συμπληρωματικού οξυγόνου, χορήγηση μεγάλων ποσοτήτων ενδοφλέβιων υγρών και στενή παρακολούθηση.[3] Η επινεφρίνη είναι η θεραπεία επιλογής. Τα αντιισταμινικά και τα κορτικοστεροειδή συχνά χρησιμοποιούνται σε συνδυασμό με την επινεφρίνη.[5] Μόλις ένα άτομο επιστρέψει σε φυσιολογική κατάσταση, θα πρέπει να μεταφερθεί στο νοσοκομείο για παρακολούθηση από 2 έως 24 ώρες ώστε να επιβεβαιωθεί ότι δεν επιστρέφουν τα συμπτώματα, όπως θα μπορούσαν στην περίπτωση διφασικής αναφυλαξίας.[10][23][25][4]

Επινεφρίνη

Η επινεφρίνη (αδρεναλίνη) είναι η κύρια θεραπεία για την αναφυλαξία. Δεν υπάρχει κανένας λόγος για τον οποίο δεν πρέπει να χρησιμοποιείται (δεν υπάρχει απόλυτη αντένδειξη).[3] Συνιστάται, η χορήγηση της επινεφρίνης ενδομυϊκά στον προσθιοπλάγιο μηρό, όσο το δυνατόν συντομότερα από την στιγμή που η παρουσιαστεί υποψία αναφυλαξίας.[5] Η ένεση μπορεί να επαναλαμβάνεται κάθε 5 έως 15 λεπτά, εάν το άτομο δεν ανταποκρίνεται καλά στη θεραπεία.[5] Σε ποσοστό 16 έως 35% των περιπτώσεων είναι απαραίτητη δεύτερη δόση. [10] Σπάνια απαιτούνται περισσότερες από δύο δόσεις.[5] Η ένεση σε μύα (ενδομυϊκή χορήγηση) είναι προτιμότερη από την ένεση κάτω από το δέρμα (υποδόρια χορήγηση), όπου το φάρμακο απορροφάται πολύ αργά.[26] Μικρά προβλήματα από την επινεφρίνη περιλαμβάνουν τρέμουλο, άγχος, πονοκεφάλους και ταχυπαλμία.[5]

Η επινεφρίνη δεν επιδρά σε άτομα που λαμβάνουν αγωγή με β-αναστολείς.[10] Σε αυτή την περίπτωση, αν η επινεφρίνη δεν είναι αποτελεσματική, μπορεί να δοθεί ενδοφλέβια χορήγηση γλυκαγόνης. Η γλυκαγόνη έχει ένα μηχανισμό δράσης που δεν περιλαμβάνει β-υποδοχείς.[10]

Εάν είναι απαραίτητο, η επινεφρίνη μπορεί επίσης να χορηγηθεί με ενδοφλέβια ένεση (ενδοφλέβια έγχυση) χρησιμοποιώντας αραιό διάλυμα. Η ενδοφλέβια επινεφρίνη, ωστόσο, έχει συνδεθεί με τις καρδιακές αρρυθμίες (δυσρυθμία) και τα καρδιακά επεισόδια (έμφραγμα του μυοκαρδίου).[27] Οι προγεμισμένες ενέσεις επινεφρίνης, οι οποίες επιτρέπουν στα άτομα με αναφυλαξία να χορηγήσουν οι ίδιοι την ένεση επινεφρίνης σε ένα μυ τους, είναι συνήθως διαθέσιμες σε δύο δόσεις, μία για ενήλικες ή παιδιά που ζυγίζουν περισσότερο από 25 kg και μία για τα παιδιά που ζυγίζουν από 10 έως 25 kg.[28]

Προσθήκες

Τα αντιισταμινικά συνήθως χρησιμοποιούνται συμπληρωματικά μαζί με την επινεφρίνη. Στη θεωρία είχε θεωρηθεί ότι θα ήταν αποτελεσματικά, αλλά υπάρχουν πολύ λίγα στοιχεία που αποδεικνύουν ότι πράγματι τα αντιισταμινικά είναι αποτελεσματικά στην αντιμετώπιση της αναφυλαξίας. Η ανασκόπηση Cochrane 2007 δεν βρήκε καλής ποιότητας μελέτες που θα μπορούσαν να χρησιμοποιηθούν για να στηρίξει τη χρήση τους. [29] Τα αντιισταμινικά δεν θεωρείται ότι έχουν κάποια επίδραση στη συσσώρευση υγρού ή στους σπασμούς των αεραγωγών.[10] Τα κορτικοστεροειδή είναι απίθανο να κάνουν διαφορά εάν ένα άτομο παρουσιάζει επεισόδιο αναφυλαξίας. Μπορούν να χρησιμοποιηθούν με την ελπίδα μείωσης του κινδύνου διφασικής αναφυλαξίας, αλλά η αποτελεσματικότητά τους στην πρόληψη της μελλοντικής αναφυλαξίας είναι επισφαλής.[23] Η σαλβουταμόλη που δίνεται μέσω μιας αναπνευστικής συσκευής (νεφελοποιητής) μπορεί να είναι αποτελεσματική όταν η επινεφρίνη δεν ανακουφίζει τα συμπτώματα βρογχόσπασμου.[10] Το κυανό του μεθυλενίου έχει χρησιμοποιηθεί σε εκείνους που δεν ανταποκρίνονται σε άλλα μέτρα, επειδή μπορεί να χαλαρώσει λείες μυϊκές ίνες.[10]

Προετοιμασία

Τα άτομα που κινδυνεύουν από αναφυλαξία συνιστάται να έχουν ένα “σχέδιο δράσης”. Οι γονείς θα πρέπει να ενημερώσουν τα σχολεία για τις αλλεργίες των παιδιών τους καθώς και για τις ενέργειες που θα πρέπει να πραγματοποιηθούν σε περίπτωση επείγοντος περιστατικού αναφυλακτικής αντίδρασης.[30] Το σχέδιο δράσης περιλαμβάνει συνήθως τη χρήση ενέσεων εφόδου επινεφρίνης, τη σύσταση να φορούν ένα βραχιόλι ιατρικής προειδοποίησης και τη παροχή συμβουλών για την αποφυγή πιθανής πρόκλησης.[30] Είναι διαθέσιμες θεραπείες ώστε να καταστεί το σώμα λιγότερο ευαίσθητο στην ουσία που προκαλεί την αλλεργική αντίδραση (ανοσοθεραπεία αλλεργιογόνου). Αυτός ο τύπος της θεραπείας μπορεί να αποτρέψει μελλοντικά επεισόδια αναφυλαξίας. Ένας πολυετής κύκλος υποδόριας απευαισθητοποίησης έχει αποδειχθεί αποτελεσματικός κατά των εντόμων, ενώ η από του στόματος απευαισθητοποίηση είναι αποτελεσματική για πολλά τρόφιμα.[3]

Προοπτική

Υπάρχει μια καλή πιθανότητα αποκατάστασης όταν η αιτία είναι γνωστή και το άτομο λαμβάνει άμεση θεραπεία.[31] Ακόμη κι εάν η αιτία είναι άγνωστη, εφόσον το φάρμακο είναι διαθέσιμο για να σταματήσει την αντίδραση, το άτομο συνήθως αναρρώνει.[4] Σε περιπτώσεις θανάτου, το γεγονός αυτό συνήθως οφείλεται είτε σε μια αναπνευστική αιτία (κατά κύριο λόγο η απόφραξη των αεραγωγών) ή σε καρδιαγγειακή αιτία (σοκ).[10][22] Η αναφυλαξία προκαλεί το θάνατο από το 0,7 έως το 20% των περιπτώσεων.[4][9] Ορισμένοι θάνατοι έχουν σημειωθεί μέσα σε λίγα λεπτά.[5] Οι άνθρωποι που έχουν ήδη περάσει αναφυλαξία συνήθως έχουν καλά αποτελέσματα, με μικρότερου αριθμού και λιγότερο σοβαρά επεισόδια καθώς μεγαλώνουν.[32]

Πιθανότητες

Η συχνότητα εμφάνισης της αναφυλαξίας είναι 4 με 5 φορές ανά 100.000 άτομα ετησίωςς,[10] με κίνδυνο ζωής της τάξης του 0,5% έως 2%.[5] Τα ποσοστά φαίνεται να αυξάνονται. Ο αριθμός των ανθρώπων με αναφυλαξία στη δεκαετία του 1980 ήταν περίπου 20 ανά 100.000 ετησίως, ενώ στη δεκαετία του 1990 ήταν 50 ανά 100.000 ανά έτος.[3] Η αύξηση φαίνεται να αφορά κατά κύριο λόγο στην αναφυλαξία που προκαλείται από τη λήψη τροφής.[33] Ο κίνδυνος είναι μεγαλύτερος στους νέους και στις γυναίκες.[3][10]

Επί του παρόντος, η αναφυλαξία προκαλεί 500-1.000 θανάτους ανά έτος (2,4 ανά εκατομμύριο) στις Ηνωμένες Πολιτείες, 20 θανάτους ανά έτος στο Ηνωμένο Βασίλειο (0,33 ανά εκατομμύριο) και 15 θανάτους ανά έτος στην Αυστραλία (0,64 ανά εκατομμύριο).[10] Τα ποσοστά θνησιμότητας μειώθηκαν μεταξύ των ετών 1970 και 2000.[34] Στην Αυστραλία, οι θάνατοι από αναφυλαξία που οφείλεται στα τρόφιμα αφορά κυρίως γυναίκες, ενώ οι θάνατοι που οφείλονται σε τσιμπήματα εντόμων αφορούν κυρίως άνδρες.[10] Οι θάνατοι από αναφυλαξία οφείλονται συχνότερα σε φάρμακα.[10]

Ιστορικό

Ο όρος “aphylaxis” (αφυλαξία) επινοήθηκε από τον Charles Richet το 1902 και αργότερα άλλαξε σε “αναφυλαξία” επειδή ακουγόταν καλύτερα.[11] Το 1913, του απονεμήθηκε το βραβείο Νόμπελ Ιατρικής και Φυσιολογίας για το έργο του σε ό,τι αφορά την αναφυλαξία.[4] Ωστόσο, η ίδια η αντίδραση έχει αναφερθεί από την αρχαιότητα.[24] Ο όρος προέρχεται από την ελληνική γλώσσα | ελληνικές λέξεις «ἀνά» δηλ. «κατά» και «φύλαξις» δηλ. «προστασία».[35]

Έρευνα

Σε εξέλιξη βρίσκονται προσπάθειες για την ανάπτυξη επινεφρίνης, η οποία θα μπορεί να χορηγηθεί υπογλώσσια (υπογλώσσια επινεφρίνη) για την αντιμετώπιση της αναφυλαξίας.[10] Η υποδόρια ένεση του αντι-IgE αντισώματος omalizumab (ομαλιζουμάμπη) μελετάται ως μέθοδος για την πρόληψη υποτροπής, ωστόσο δε συνιστάται ακόμη η χρήση της.[5][36]

Αναφορές

- ↑ 1,0 1,1 Tintinalli, Judith E. (2010). Emergency Medicine: A Comprehensive Study Guide (Emergency Medicine (Tintinalli)). New York: McGraw-Hill Companies. σελ. 177–182. ISBN 0-07-148480-9.

- ↑ Oswalt ML, Kemp SF (May 2007). “Anaphylaxis: office management and prevention”. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am 27 (2): 177–91, vi. doi:. PMID 17493497. “Clinically, anaphylaxis is considered likely to be present if any one of three criteria is satisfied within minutes to hours”.

- ↑ 3,00 3,01 3,02 3,03 3,04 3,05 3,06 3,07 3,08 3,09 3,10 3,11 Simons FE (October 2009). “Anaphylaxis: Recent advances in assessment and treatment”. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 124 (4): 625–36; quiz 637–8. doi:. PMID 19815109.

- ↑ 4,00 4,01 4,02 4,03 4,04 4,05 4,06 4,07 4,08 4,09 4,10 4,11 4,12 4,13 4,14 Marx, John (2010). Rosen’s emergency medicine: concepts and clinical practice 7th edition. Philadelphia, PA: Mosby/Elsevier. σελ. 15111528. ISBN 9780323054720.

- ↑ 5,00 5,01 5,02 5,03 5,04 5,05 5,06 5,07 5,08 5,09 5,10 5,11 5,12 5,13 5,14 5,15 5,16 5,17 5,18 5,19 5,20 5,21 5,22 5,23 5,24 Simons, FE (2010 May). “World Allergy Organization survey on global availability of essentials for the assessment and management of anaphylaxis by allergy-immunology specialists in health care settings.”. Annals of allergy, asthma & immunology : official publication of the American College of Allergy, Asthma, & Immunology 104 (5): 405–12. PMID 20486330.

- ↑ 6,0 6,1 6,2 6,3 Sampson HA, Muñoz-Furlong A, Campbell RL, et al. (February 2006). “Second symposium on the definition and management of anaphylaxis: summary report—Second National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease/Food Allergy and Anaphylaxis Network symposium”. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 117 (2): 391–7. doi:. PMID 16461139.

- ↑ 7,0 7,1 7,2 Limsuwan, T (2010 Jul). “Acute symptoms of drug hypersensitivity (urticaria, angioedema, anaphylaxis, anaphylactic shock).”. The Medical clinics of North America 94 (4): 691–710, x. PMID 20609858.

- ↑ 8,0 8,1 8,2 8,3 8,4 8,5 Brown, SG (2006 Sep 4). “Anaphylaxis: diagnosis and management.”. The Medical journal of Australia 185 (5): 283–9. PMID 16948628.

- ↑ 9,0 9,1 9,2 9,3 9,4 Triggiani, M (2008 Sep). “Allergy and the cardiovascular system.”. Clinical and experimental immunology 153 Suppl 1: 7–11. PMID 18721322. PMC 2515352.

- ↑ 10,00 10,01 10,02 10,03 10,04 10,05 10,06 10,07 10,08 10,09 10,10 10,11 10,12 10,13 10,14 10,15 10,16 10,17 10,18 10,19 10,20 10,21 10,22 10,23 10,24 10,25 Lee, JK (2011 Jul). “Anaphylaxis: mechanisms and management.”. Clinical and experimental allergy : journal of the British Society for Allergy and Clinical Immunology 41 (7): 923–38. PMID 21668816.

- ↑ 11,0 11,1 11,2 11,3 11,4 11,5 11,6 Boden, SR (2011 Jul). “Anaphylaxis: a history with emphasis on food allergy.”. Immunological reviews 242 (1): 247–57. PMID 21682750.

- ↑ Worm, M (2010). “Epidemiology of anaphylaxis.”. Chemical immunology and allergy 95: 12–21. PMID 20519879.

- ↑ 13,0 13,1 editors, Marianne Gausche-Hill, Susan Fuchs, Loren Yamamoto, (2007). The pediatric emergency medicine resource (Rev. 4. ed. έκδοση). Sudbury, Mass.: Jones & Bartlett. σελ. 69. ISBN 9780763744144.

- ↑ Dewachter, P (2009 Nov). “Anaphylaxis and anesthesia: controversies and new insights.”. Anesthesiology 111 (5): 1141–50. doi:. PMID 19858877.

- ↑ editor, Mariana C. Castells, (2010). Anaphylaxis and hypersensitivity reactions. New York: Humana Press. σελ. 223. ISBN 9781603279505.

- ↑ 16,0 16,1 16,2 Volcheck, Gerald W. (2009). Clinical allergy : diagnosis and management. Totowa, N.J.: Humana Press. σελ. 442. ISBN 9781588296160.

- ↑ 17,0 17,1 Drain, KL (2001). “Preventing and managing drug-induced anaphylaxis.”. Drug safety : an international journal of medical toxicology and drug experience 24 (11): 843–53. PMID 11665871.

- ↑ Klotz, JH (2010 Jun 15). “”Kissing bugs”: potential disease vectors and cause of anaphylaxis.”. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America 50 (12): 1629–34. PMID 20462351.

- ↑ Bilò, MB (2011 Jul). “Anaphylaxis caused by Hymenoptera stings: from epidemiology to treatment.”. Allergy 66 Suppl 95: 35–7. PMID 21668850.

- ↑ Cox, L (2010 Mar). “Speaking the same language: The World Allergy Organization Subcutaneous Immunotherapy Systemic Reaction Grading System.”. The Journal of allergy and clinical immunology 125 (3): 569–74, 574.e1-574.e7. PMID 20144472.

- ↑ Bilò, BM (2008 Aug). “Epidemiology of insect-venom anaphylaxis.”. Current opinion in allergy and clinical immunology 8 (4): 330–7. PMID 18596590.

- ↑ 22,0 22,1 22,2 22,3 22,4 22,5 Khan, BQ (2011 Aug). “Pathophysiology of anaphylaxis.”. Current opinion in allergy and clinical immunology 11 (4): 319–25. PMID 21659865.

- ↑ 23,0 23,1 23,2 Lieberman P (September 2005). “Biphasic anaphylactic reactions”. Ann. Allergy Asthma Immunol. 95 (3): 217–26; quiz 226, 258. doi:. PMID 16200811.

- ↑ 24,0 24,1 24,2 24,3 Ring, J (2010). “History and classification of anaphylaxis.”. Chemical immunology and allergy 95: 1–11. PMID 20519878.

- ↑ Emergency treatment of anaphylactic reactions – Guidelines for healthcare providers (PDF). Resuscitation Council (UK). January 2008. Ανακτήθηκε στις 2008-04-22.

- ↑ Simons, KJ (2010 Aug). “Epinephrine and its use in anaphylaxis: current issues.”. Current opinion in allergy and clinical immunology 10 (4): 354–61. PMID 20543673.

- ↑ Mueller, UR (2007 Aug). “Cardiovascular disease and anaphylaxis.”. Current opinion in allergy and clinical immunology 7 (4): 337–41. PMID 17620826.

- ↑ Sicherer, SH (2007 Mar). “Self-injectable epinephrine for first-aid management of anaphylaxis.”. Pediatrics 119 (3): 638–46. PMID 17332221.

- ↑ Sheikh A, Ten Broek V, Brown SG, Simons FE (August 2007). “H1-antihistamines for the treatment of anaphylaxis: Cochrane systematic review”. Allergy 62 (8): 830–7. doi:. PMID 17620060.

- ↑ 30,0 30,1 Martelli, A (2008 Aug). “Anaphylaxis in the emergency department: a paediatric perspective.”. Current opinion in allergy and clinical immunology 8 (4): 321–9. PMID 18596589.

- ↑ Harris, edited by Jeffrey; Weisman, Micheal S. (2007). Head and neck manifestations of systemic disease. London: Informa Healthcare. σελ. 325. ISBN 9780849340505.

- ↑ editor, Mariana C. Castells, (2010). Anaphylaxis and hypersensitivity reactions. New York: Humana Press. σελ. 223. ISBN 9781603279505.

- ↑ Koplin, JJ (2011 Oct). “An update on epidemiology of anaphylaxis in children and adults.”. Current opinion in allergy and clinical immunology 11 (5): 492–6. PMID 21760501.

- ↑ Demain, JG (2010 Aug). “Anaphylaxis and insect allergy.”. Current opinion in allergy and clinical immunology 10 (4): 318–22. PMID 20543675.

- ↑ anaphylaxis. merriam-webster.com. Ανακτήθηκε στις 2009-11-21.

- ↑ Vichyanond, P (2011 Sep). “Omalizumab in allergic diseases, a recent review.”. Asian Pacific journal of allergy and immunology / launched by the Allergy and Immunology Society of Thailand 29 (3): 209–19. PMID 22053590.

Από τη Βικιπαίδεια, την ελεύθερη εγκυκλοπαίδεια

http://el.wikipedia.org/wiki/%CE%91%CE%BD%CE%B1%CF%86%CF%85%CE%BB%CE%B1%CE%BE%CE%AF%CE%B1

ENGLISH

| Allergy | |

|---|---|

| Classification and external resources | |

Hives are a common allergic symptom. |

|

| ICD–10 | T78.4 |

| ICD–9 | 995.3 |

| DiseasesDB | 33481 |

| MedlinePlus | 000812 |

| eMedicine | med/1101 |

| MeSH | D006967 |

An allergy is a hypersensitivity disorder of the immune system.[1] Allergic reactions occur when a person’s immune system reacts to normally harmless substances in the environment. A substance that causes a reaction is called an allergen. These reactions are acquired, predictable, and rapid. Allergy is one of four forms of hypersensitivity and is formally called type I (or immediate) hypersensitivity. Allergic reactions are distinctive because of excessive activation of certain white blood cells called mast cells and basophils by a type of antibody called Immunoglobulin E (IgE). This reaction results in an inflammatory response which can range from uncomfortable to dangerous.

Mild allergies like hay fever are very common in the human population and cause symptoms such as red eyes, itchiness, and runny nose, eczema, hives, or an asthma attack. Allergies can play a major role in conditions such as asthma. In some people, severe allergies to environmental or dietary allergens or to medication may result in life-threatening reactions called anaphylaxis. Food allergies, and reactions to the venom of stinging insects such as wasps and bees are often associated with these severe reactions.[2]

A variety of tests exist to diagnose allergic conditions. If done they should be ordered and interpreted in light of a person’s history of exposure as many positive test results do not mean a clinically significant allergy.[3] Tests include placing possible allergens on the skin and looking for a reaction such as swelling and blood tests to look for an allergen-specific IgE.

Treatments for allergies include avoiding known allergens, steroids that modify the immune system in general, and medications such as antihistamines and decongestants which reduce symptoms. Many of these medications are taken by mouth, although epinephrine, which is used to treat anaphylactic reactions, is injected. Immunotherapy uses injected allergens to desensitize the body’s response.

Signs and symptoms

| Affected organ | Symptom |

|---|---|

| Nose | swelling of the nasal mucosa (allergic rhinitis) |

| Sinuses | allergic sinusitis |

| Eyes | redness and itching of the conjunctiva (allergic conjunctivitis) |

| Airways | Sneezing, coughing, bronchoconstriction, wheezing and dyspnea, sometimes outright attacks of asthma, in severe cases the airway constricts due to swelling known as laryngeal edema |

| Ears | feeling of fullness, possibly pain, and impaired hearing due to the lack of eustachian tube drainage. |

| Skin | rashes, such as eczema and hives (urticaria) |

| Gastrointestinal tract | abdominal pain, bloating, vomiting, diarrhea |

Many allergens such as dust or pollen are airborne particles. In these cases, symptoms arise in areas in contact with air, such as eyes, nose, and lungs. For instance, allergic rhinitis, also known as hay fever, causes irritation of the nose, sneezing, itching, and redness of the eyes.[4] Inhaled allergens can also lead to asthmatic symptoms, caused by narrowing of the airways (bronchoconstriction) and increased production of mucus in the lungs, shortness of breath (dyspnea), coughing and wheezing.[5]

Aside from these ambient allergens, allergic reactions can result from foods, insect stings, and reactions to medications like aspirin and antibiotics such as penicillin. Symptoms of food allergy include abdominal pain, bloating, vomiting, diarrhea, itchy skin, and swelling of the skin during hives. Food allergies rarely cause respiratory (asthmatic) reactions, or rhinitis.[6] Insect stings, antibiotics, and certain medicines produce a systemic allergic response that is also called anaphylaxis; multiple organ systems can be affected, including the digestive system, the respiratory system, and the circulatory system.[7][8][9] Depending on the rate of severity, it can cause cutaneous reactions, bronchoconstriction, edema, hypotension, coma, and even death. This type of reaction can be triggered suddenly, or the onset can be delayed. The severity of this type of allergic response often requires injections of epinephrine, sometimes through a device known as the EpiPen or Twinject auto-injector. The nature of anaphylaxis is such that the reaction can seem to be subsiding, but may recur throughout a prolonged period of time.[9]

Substances that come into contact with the skin, such as latex, are also common causes of allergic reactions, known as contact dermatitis or eczema.[10] Skin allergies frequently cause rashes, or swelling and inflammation within the skin, in what is known as a “wheal and flare” reaction characteristic of hives and angioedema.[11]

Cause

Risk factors for allergy can be placed in two general categories, namely host and environmental factors.[12] Host factors include heredity, gender, race, and age, with heredity being by far the most significant. However, there have been recent increases in the incidence of allergic disorders that cannot be explained by genetic factors alone. Four major environmental candidates are alterations in exposure to infectious diseases during early childhood, environmental pollution, allergen levels, and dietary changes.[13]

Foods

A wide variety of foods can cause allergic reactions, but 90% of allergic responses to foods are caused by cow’s milk, soy, eggs, wheat, peanuts, tree nuts, fish and shellfish.[14] Other food allergies, affecting less than 1 person per 10,000 population, may be considered “rare”.[15]

The most common food allergy, at least in the US population, is a sensitivity to crustacea.[15] Although peanut allergies are notorious for their severity, peanut allergies are not the most common food allergy in adults or children. Severe or life-threatening reactions may be triggered by other allergens and are more common when combined with asthma.[14]

Rates of allergies differ between adults and children. Peanut allergies can sometimes be outgrown by children. Egg allergies affect one to two percent of children but are outgrown by about two-thirds of children by the age of 5.[16] The sensitivity is usually to proteins in the white rather than the yolk.[17]

Milk allergies are the most prevalent in children.[18] Some sufferers are unable to tolerate milk from cows, goats, or sheep, and many sufferers are also unable to tolerate dairy products such as cheese. Lactose intolerance, a common reaction to milk, is not a form of allergy, but rather due to the absence of an enzyme in the digestive tract. A small portion of children with a milk allergy, roughly ten percent, will have a reaction to beef. Beef contains a small amount of protein that is present in cow’s milk.[19] Sufferers of tree nut allergies may be allergic to one or many tree nuts, including pecans, pistachios, pine nuts, and walnuts.[17] Also seeds, including sesame seeds and poppy seeds, contain oils where protein is present, which may elicit an allergic reaction.[17]

Non-food proteins

Latex can trigger an IgE-mediated cutaneous, respiratory, and systemic reaction. The prevalence of latex allergy in the general population is believed to be less than one percent. In a hospital study, one in 800 surgical patients (0.125 percent) report latex sensitivity, although the sensitivity among healthcare workers is higher, between seven and ten percent. Researchers attribute this higher level to the exposure of healthcare workers to areas with significant airborne latex allergens, such as operating rooms, intensive-care units, and dental suites. These latex-rich environments may sensitize healthcare workers who regularly inhale allergenic proteins.[20]

The most prevalent response to latex is an allergic contact dermatitis, a delayed hypersensitive reaction appearing as dry, crusted lesions. This reaction usually lasts 48 to 96 hours. Sweating or rubbing the area under the glove aggravates the lesions, possibly leading to ulcerations.[20] Anaphylactic reactions occur most often in sensitive patients, who have been exposed to the surgeon’s latex gloves during abdominal surgery, but other mucosal exposures, such as dental procedures, can also produce systemic reactions.[20]

Latex and banana sensitivity may cross-react; furthermore,those with latex allergy may also have sensitivities to avocado, kiwifruit, and chestnut.[21] These patients often have perioral itching and local urticaria. Only occasionally have these food-induced allergies induced systemic responses. Researchers suspect that the cross-reactivity of latex with banana, avocado, kiwifruit, and chestnut occurs because latex proteins are structurally homologous with some plant proteins.[20]

Toxins interacting with proteins

Another non-food protein reaction, urushiol-induced contact dermatitis, originates after contact with poison ivy, eastern poison oak, western poison oak, or poison sumac. Urushiol, which is not itself a protein, acts as a hapten and chemically reacts with, binds to, and changes the shape of integral membrane proteins on exposed skin cells. The immune system does not recognize the affected cells as normal parts of the body, causing a T-cell-mediated immune response.[22] Of these poisonous plants, sumac is the most virulent.[23] The resulting dermatological response to the reaction between urushiol and membrane proteins includes redness, swelling, papules, vesicles, blisters, and streaking.[24]

Estimates vary on the percentage of the population that will have an immune system response. Approximately 25 percent of the population will have a strong allergic response to urushiol. In general, approximately 80 percent to 90 percent of adults will develop a rash if they are exposed to .0050 milligrams (7.7×10−5 gr) of purified urushiol, but some people are so sensitive that it takes only a molecular trace on the skin to initiate an allergic reaction.[25]

Genetic basis

Allergic diseases are strongly familial: identical twins are likely to have the same allergic diseases about 70% of the time; the same allergy occurs about 40% of the time in non-identical twins.[26] Allergic parents are more likely to have allergic children,[27] and those children’s allergies are likely to be more severe than those in children of non-allergic parents. Some allergies, however, are not consistent along genealogies; parents who are allergic to peanuts may have children who are allergic to ragweed. It seems that the likelihood of developing allergies is inherited and related to an irregularity in the immune system, but the specific allergen is not.[27]

The risk of allergic sensitization and the development of allergies varies with age, with young children most at risk.[28] Several studies have shown that IgE levels are highest in childhood and fall rapidly between the ages of 10 and 30 years.[28] The peak prevalence of hay fever is highest in children and young adults and the incidence of asthma is highest in children under 10.[29] Overall, boys have a higher risk of developing allergies than girls,[27] although for some diseases, namely asthma in young adults, females are more likely to be affected.[30] Sex differences tend to decrease in adulthood.[27]Ethnicity may play a role in some allergies; however, racial factors have been difficult to separate from environmental influences and changes due to migration.[27] It has been suggested that different genetic loci are responsible for asthma, to be specific, in people of European, Hispanic, Asian, and African origins.[31]

Hygiene hypothesis

Allergic diseases are caused by inappropriate immunological responses to harmless antigens driven by a TH2-mediated immune response. Many bacteria and viruses elicit a TH1-mediated immune response, which down-regulates TH2 responses. The first proposed mechanism of action of the hygiene hypothesis was that insufficient stimulation of the TH1 arm of the immune system leads to an overactive TH2 arm, which in turn leads to allergic disease.[32] In other words, individuals living in too sterile an environment are not exposed to enough pathogens to keep the immune system busy. Since our bodies evolved to deal with a certain level of such pathogens, when they are not exposed to this level, the immune system will attack harmless antigens and thus normally benign microbial objects — like pollen — will trigger an immune response.[33]

The hygiene hypothesis was developed to explain the observation that hay fever and eczema, both allergic diseases, were less common in children from larger families, which were, it is presumed, exposed to more infectious agents through their siblings, than in children from families with only one child. The hygiene hypothesis has been extensively investigated by immunologists and epidemiologists and has become an important theoretical framework for the study of allergic disorders. It is used to explain the increase in allergic diseases that have been seen since industrialization, and the higher incidence of allergic diseases in more developed countries. The hygiene hypothesis has now expanded to include exposure to symbiotic bacteria and parasites as important modulators of immune system development, along with infectious agents.

Epidemiological data support the hygiene hypothesis. Studies have shown that various immunological and autoimmune diseases are much less common in the developing world than the industrialized world and that immigrants to the industrialized world from the developing world increasingly develop immunological disorders in relation to the length of time since arrival in the industrialized world.[34] Longitudinal studies in the third world demonstrate an increase in immunological disorders as a country grows more affluent and, it is presumed, cleaner.[35] The use of antibiotics in the first year of life has been linked to asthma and other allergic diseases.[36] The use of antibacterial cleaning products has also been associated with higher incidence of asthma, as has birth by Caesarean section rather than vaginal birth.[37][38]

Other environmental factors

International differences have been associated with the number of individuals within a population that suffer from allergy. Allergic diseases are more common in industrialized countries than in countries that are more traditional or agricultural, and there is a higher rate of allergic disease in urban populations versus rural populations, although these differences are becoming less defined.[39]

Exposure to allergens, especially in early life, is an important risk factor for allergy. Alterations in exposure to microorganisms is another plausible explanation, at present, for the increase in atopic allergy.[13] Endotoxin exposure reduces release of inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α, IFNγ, interleukin-10, and interleukin-12 from white blood cells (leukocytes) that circulate in the blood.[40] Certain microbe-sensing proteins, known as Toll-like receptors, found on the surface of cells in the body are also thought to be involved in these processes.[41]

Gutworms and similar parasites are present in untreated drinking water in developing countries, and were present in the water of developed countries until the routine chlorination and purification of drinking water supplies.[42] Recent research has shown that some common parasites, such as intestinal worms (e.g., hookworms), secrete chemicals into the gut wall (and, hence, the bloodstream) that suppress the immune system and prevent the body from attacking the parasite.[43] This gives rise to a new slant on the hygiene hypothesis theory — that co-evolution of man and parasites has led to an immune system that functions correctly only in the presence of the parasites. Without them, the immune system becomes unbalanced and oversensitive.[44] In particular, research suggests that allergies may coincide with the delayed establishment of gut flora in infants.[45] However, the research to support this theory is conflicting, with some studies performed in China and Ethiopia showing an increase in allergy in people infected with intestinal worms.[39] Clinical trials have been initiated to test the effectiveness of certain worms in treating some allergies.[46] It may be that the term ‘parasite’ could turn out to be inappropriate, and in fact a hitherto unsuspected symbiosis is at work.[46] For more information on this topic, see Helminthic therapy.

Pathophysiology

Acute response

In the early stages of allergy, a type I hypersensitivity reaction against an allergen encountered for the first time and presented by a professional Antigen-Presenting Cell causes a response in a type of immune cell called a TH2 lymphocyte, which belongs to a subset of T cells that produce a cytokine called interleukin-4 (IL-4). These TH2 cells interact with other lymphocytes called B cells, whose role is production of antibodies. Coupled with signals provided by IL-4, this interaction stimulates the B cell to begin production of a large amount of a particular type of antibody known as IgE. Secreted IgE circulates in the blood and binds to an IgE-specific receptor (a kind of Fc receptor called FcεRI) on the surface of other kinds of immune cells called mast cells and basophils, which are both involved in the acute inflammatory response. The IgE-coated cells, at this stage, are sensitized to the allergen.[13]

If later exposure to the same allergen occurs, the allergen can bind to the IgE molecules held on the surface of the mast cells or basophils. Cross-linking of the IgE and Fc receptors occurs when more than one IgE-receptor complex interacts with the same allergenic molecule, and activates the sensitized cell. Activated mast cells and basophils undergo a process called degranulation, during which they release histamine and other inflammatory chemical mediators (cytokines, interleukins, leukotrienes, and prostaglandins) from their granules into the surrounding tissue causing several systemic effects, such as vasodilation, mucous secretion, nerve stimulation, and smooth muscle contraction. This results in rhinorrhea, itchiness, dyspnea, and anaphylaxis. Depending on the individual, allergen, and mode of introduction, the symptoms can be system-wide (classical anaphylaxis), or localized to particular body systems; asthma is localized to the respiratory system and eczema is localized to the dermis.[13]

Late-phase response

After the chemical mediators of the acute response subside, late-phase responses can often occur. This is due to the migration of other leukocytes such as neutrophils, lymphocytes, eosinophils and macrophages to the initial site. The reaction is usually seen 2–24 hours after the original reaction.[47] Cytokines from mast cells may play a role in the persistence of long-term effects. Late-phase responses seen in asthma are slightly different from those seen in other allergic responses, although they are still caused by release of mediators from eosinophils and are still dependent on activity of TH2 cells.[48]

Diagnosis

Effective management of allergic diseases relies on the ability to make an accurate diagnosis.[49] Allergy testing can help confirm or rule out allergies.[50][51] Correct diagnosis, counseling and avoidance advice based on valid allergy test results will help reduce the incidence of symptoms, medications and improve quality of life.[50] For assessing the presence of allergen-specific IgE antibodies, two different methods can be used: a skin prick test or an allergy blood test. Both methods are recommended and have similar diagnostic value.[51][52]

Skin prick tests and blood tests are equally cost-effective and health economic evidence show that both the IgE antibody test and the skin prick test were cost effective compared with no test.[50] Also, earlier and more accurate diagnoses save cost due to reduced consultations, referrals to secondary care, misdiagnosis and emergency admissions.[53]

Allergy undergoes dynamic changes over time. Regular allergy testing of relevant allergens provides information on if and how patient management can be changed, in order to improve health and quality of life. Annual testing is often the practice for determining whether allergy to milk, egg, soy, and wheat have been outgrown and the testing interval is extended to 2 to 3 years for allergy to peanut, tree nuts, fish, and crustacean shellfish.[51] Results of follow-up testing can guide decision-making regarding whether and when it is safe to introduce or re-introduce allergenic food into the diet.[54]

Skin testing

Skin testing is also known as “puncture testing” and “prick testing” due to the series of tiny puncture or pricks made into the patient’s skin. Small amounts of suspected allergens and/or their extracts (pollen, grass, mite proteins, peanut extract, etc.) are introduced to sites on the skin marked with pen or dye (the ink/dye should be carefully selected, lest it cause an allergic response itself). A small plastic or metal device is used to puncture or prick the skin. Sometimes, the allergens are injected “intradermally” into the patient’s skin, with a needle and syringe. Common areas for testing include the inside forearm and the back. If the patient is allergic to the substance, then a visible inflammatory reaction will usually occur within 30 minutes. This response will range from slight reddening of the skin to a full-blown hive (called “wheal and flare”) in more sensitive patients similar to a mosquito bite. Interpretation of the results of the skin prick test is normally done by allergists on a scale of severity, with +/- meaning borderline reactivity, and 4+ being a large reaction. Increasingly, allergists are measuring and recording the diameter of the wheal and flare reaction. Interpretation by well-trained allergists is often guided by relevant literature.[55] Some patients may believe they have determined their own allergic sensitivity from observation, but a skin test has been shown to be much better than patient observation to detect allergy.[56]

If a serious life threatening anaphylactic reaction has brought a patient in for evaluation, some allergists will prefer an initial blood test prior to performing the skin prick test. Skin tests may not be an option if the patient has widespread skin disease or has taken antihistamines sometime the last several days.

Blood testing

An allergy blood test is quick and simple and can be ordered by a licensed health care provider e.g. an allergy specialist, GP or PED. Unlike skin-prick testing, a blood test can be performed irrespective of age, skin condition, medication, symptom, disease activity and pregnancy. Adults and children of any age can take an allergy blood test. For babies and very young children, a single needle stick for allergy blood testing is often more gentle than several skin tests.

An allergy blood test is available through most laboratories, and a sample of the patient’s blood is sent to a laboratory for analysis and the results are sent back a few days later. Multiple allergens can be detected with a single blood sample.

Allergy blood tests are very safe, since the person is not exposed to any allergens during the testing procedure.

The test measures the concentration of specific IgE antibodies in the blood. Quantitative IgE test results increase the possibility of ranking how different substances may affect symptoms. A general rule of thumb is that the higher the IgE antibody value, the greater the likelihood of symptoms. Allergens found at low levels that today do not result in symptoms can nevertheless help predict future symptom development. The quantitative allergy blood result can help determine what a patient is allergic to, help predict and follow the disease development, estimate the risk of a severe reaction and explain cross-reactivity.[57][58]

A low total IgE level is not adequate to rule out sensitization to commonly inhaled allergens.[59]Statistical methods, such as ROC curves, predictive value calculations, and likelihood ratios have been used to examine the relationship of various testing methods to each other. These methods have shown that patients with a high total IgE have a high probability of allergic sensitization, but further investigation with allergy tests for specific IgE antibodies for a carefully chosen of allergens is often warranted.

Other

Challenge testing: Challenge testing is when small amounts of a suspected allergen are introduced to the body orally, through inhalation, or other routes. Except for testing food and medication allergies, challenges are rarely performed. When this type of testing is chosen, it must be closely supervised by an allergist.

Elimination/Challenge tests: This testing method is used most often with foods or medicines. A patient with a suspected allergen is instructed to modify his/her diet to totally avoid that allergen for determined time. If the patient experiences significant improvement, he/she may then be “challenged” by reintroducing the allergen to see if symptoms can be reproduced.

Patch testing: Patch testing is used to help ascertain the cause of skin contact allergy, or contact dermatitis. Adhesive patches, usually treated with a number of common allergic chemicals or skin sensitizers, are applied to the back. The skin is then examined for possible local reactions at least twice, usually at 48 hours after application of the patch and again two or three days later.

Unreliable tests: There are other types of allergy testing methods that the that are unreliable including applied kinesiology (allergy testing through muscle relaxation), cytotoxicity testing, urine autoinjection, skin titration (Rinkel method), and provocative and neutralization (subcutaneous) testing or sublingual provocation.[60]

Differential diagnosis

Before a diagnosis of allergic disease can be confirmed, other possible causes of the presenting symptoms should be considered.[61]Vasomotor rhinitis, for example, is one of many maladies that shares symptoms with allergic rhinitis, underscoring the need for professional differential diagnosis.[62] Once a diagnosis of asthma, rhinitis, anaphylaxis, or other allergic disease has been made, there are several methods for discovering the causative agent of that allergy.

Management

In recent times, there have been enormous improvements in the medical practices used to treat allergic conditions. With respect to anaphylaxis and hypersensitivity reactions to foods, drugs, and insects and in allergic skin diseases, advances have included the identification of food proteins to which IgE binding is associated with severe reactions and development of low-allergen foods, improvements in skin prick test predictions; evaluation of the atopy patch test; in wasp sting outcomes predictions and a rapidly disintegrating epinephrine tablet, and anti-IL-5 for eosinophilic diseases.[63]

Traditional treatment and management of allergies consisted simply of avoiding the allergen in question or otherwise reducing exposure. For instance, people with cat allergies were encouraged to avoid them. However, while avoidance of allergens may reduce symptoms and avoid life-threatening anaphylaxis, it is difficult to achieve for those with pollen or similar air-borne allergies. Nonetheless, strict avoidance of allergens is still considered a useful treatment method, and is often used in managing food allergies.

New technology approaches to decreasing IgE overproduction, and regulating histamine release in allergic individuals have demonstrated statistically significant reduction on Total Nasal Symptom Scores.[64][65]

Medication

Several antagonistic drugs are used to block the action of allergic mediators, or to prevent activation of cells and degranulation processes. These include antihistamines, glucocorticoids, epinephrine (adrenaline), theophylline and cromolyn sodium. Anti-leukotrienes, such as Montelukast (Singulair) or Zafirlukast (Accolate), are FDA approved for treatment of allergic diseases.[citation needed] Anti-cholinergics, decongestants, mast cell stabilizers, and other compounds thought to impair eosinophil chemotaxis, are also commonly used. These drugs help to alleviate the symptoms of allergy, and are imperative in the recovery of acute anaphylaxis, but play little role in chronic treatment of allergic disorders.

Immunotherapy

Desensitization or hyposensitization is a treatment in which the person is gradually vaccinated with progressively larger doses of the allergen in question. This can either reduce the severity or eliminate hypersensitivity altogether. It relies on the progressive skewing of IgG antibody production, to block excessive IgE production seen in atopys.[66] In a sense, the person builds up immunity to increasing amounts of the allergen in question. Studies have demonstrated the long-term efficacy and the preventive effect of immunotherapy in reducing the development of new allergy.[67] Meta-analyses have also confirmed efficacy of the treatment in allergic rhinitis in children[68] and in asthma.[69] A review by the Mayo Clinic in Rochester confirmed the safety and efficacy of allergen immunotherapy for allergic rhinitis and conjunctivitis, allergic forms of asthma, and stinging insect based on numerous well-designed scientific studies.[70] In addition, national and international guidelines confirm the clinical efficacy of injection immunotherapy in rhinitis and asthma, as well as the safety, provided that recommendations are followed.[71]

A second form of immunotherapy involves the intravenous injection of monoclonal anti-IgE antibodies. These bind to free and B-cell associated IgE; signalling their destruction. They do not bind to IgE already bound to the Fc receptor on basophils and mast cells, as this would stimulate the allergic inflammatory response. The first agent of this class is Omalizumab. While this form of immunotherapy is very effective in treating several types of atopy, it should not be used in treating the majority of people with food allergies.[citation needed]